-

Page Navigation Links:

- Skip to Site Navigation Links

- Skip to Features

- The University of Iowa

- Spectator

- Monthly News for UI Alumni and Friends

Training students to be professional communicators is like trying to hit a moving target. Journalism and mass communication schools across the country are revamping their curricula to prepare students for the diversified demands of the profession.

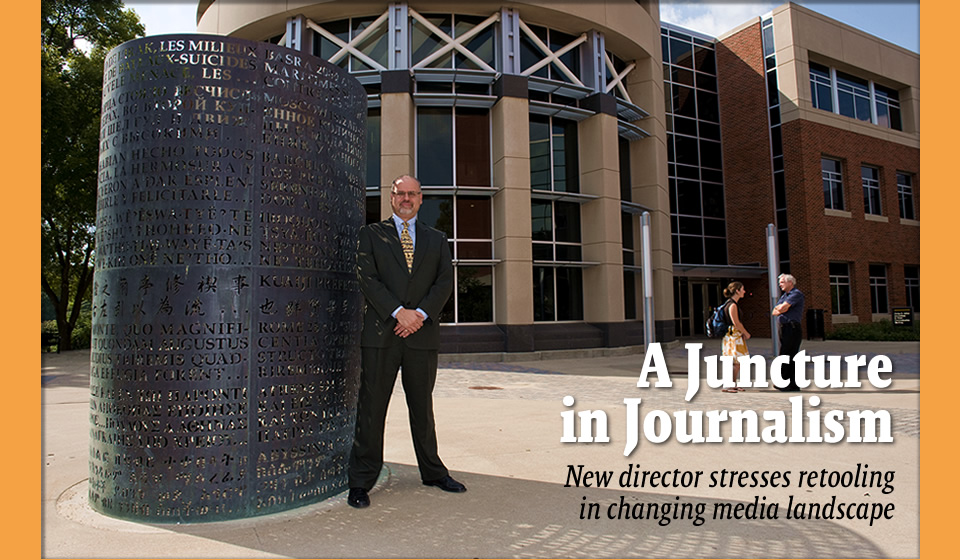

David D. Perlmutter (above, left), the new director of the University of Iowa School of Journalism and Mass Communication, took a moment to discuss his vision for the program and to offer some tips for alumni in the field. He explains how he landed at Iowa—and describes his rare but useful disorder: “information panic.”

Journalism and mass communication is changing rapidly—what’s your take on the profession? Any advice for alumni who may be concerned about their future in the field?

Twenty years ago, for example, we trained someone to be “the camera guy,” to carry a big heavy camera around and shoot video. He may have done some producing and writing, but mainly he could focus on one thing because people had the luxury to specialize within a career for a lifetime.

Now you have to be able to do everything and anticipate what your employer’s going to ask you to do tomorrow—including changing your area of specialization. The reality is that if you can’t, you will be replaced by someone who can. The days of earning a degree and being done with your education are over. Journalists need to constantly retool and retrain—to be adaptable and innovative by taking additional courses or learning on the job. If people in your office think of you as the go-to person for what’s new, I bet they’ll keep you around.

What is the UI School of Journalism and Mass Communication doing to respond to the changing media environment?

Every journalism and mass communication school in the world is asking itself “What are we doing, and how can we do it better?” The core skills remain vital and relevant— integrity and ethics; sourcing and interviewing; research; written, oral, and visual storytelling; the ability to work under deadline—and of course we’ll continue to teach them. But we are starting from scratch and evaluating the entire curriculum. We have to be brave enough to say, “let’s get rid of X,” even if we’ve done “X” for 20 years.

We and other journalism and mass communication schools are entering a period of experimentation. In a chemistry department, they understand that part of innovation is experimentation (including failures and trying again), and we need to take the same approach. We’ll be getting feedback from our students and professionals in the field to determine what our graduates need to be successful, and we will be developing curriculum in concert with industry and entrepreneurs including our own students.

I’m also very interested in having our alumni back every few years for short continuing education courses or workshops. We tend to be four-year-degree focused, but this would be one way to help alumni keep their skills fresh, and we could learn a lot from them in the process.

What are some of your favorite media?

I love books—the printed, paper kind. I get my news from newspapers, news websites, and spending a half hour or so a day on Facebook seeing what my friends are up to. My family and I watch a lot of YouTube.

Tell us about your background and how you landed here.

My parents were both professors, and I was born in Switzerland, where they were teaching. When I was about 8, my father accepted a job at the University of Pennsylvania, so I spent the rest of my childhood in Philadelphia. I went to Penn for my BA and MA. I got my PhD from the University of Minnesota, taught at Louisiana State University for 10 years, and taught at the University of Kansas for three years. My wife is from Iowa, and because I love political communication, being at the epicenter of presidential campaigns every four years will lead to some interesting projects.

You write “P&T Confidential,” a popular monthly column for The Chronicle of Higher Education. What topics do you cover?

It’s mainly about promotion and tenure. We often say in this business that we do an outstanding job of training doctoral students to be researchers, an adequate job of teaching them to be teachers, but a terrible job training them to be professors. Many times the brightest doctoral students find themselves floundering very quickly in their first job because the human relations issues and politics catch them off guard. I cover topics like getting along with colleagues, time management, and job searches.

Your research interests have ranged from pictures to politics—and even the show The Office. Could you elaborate?

I’ve studied pictures that might be classified as political, specifically emblematic photos and how they represent a complex event or time. If you say the word Tiananmen, people think of the man standing in front of the tank. Or Iwo Jima, you think of the Marines raising the flag. Then I became interested in blogs on persuasion and politics, and I published a book on political blogging, Blogwars. I’m a big fan of the show The Office, and it has led to a new research interest: the portrayal of work in the media.

What’s something people would be surprised to know about you?

I suffer from an undiagnosed and unofficially recognized disorder called “information panic.” I wake up in the morning and think, “The Vikings in Greenland—I don’t know anything about the Vikings in Greenland. I must know more about the Vikings in Greenland.” So I go off to the library and check out every book on that topic. And then once I have the Vikings in Greenland covered, I wake up and say, “Abraham Lincoln, I don’t know enough about him.” It’s a cycle—every four or five weeks I have a new information panic. People find it surprising when they bring up something obscure and I know a little about it.

—Nicole Riehl

with photo by Kirk Murray

© The University of Iowa 2009