-

Page Navigation Links:

- Skip to Site Navigation Links

- Skip to Features

- The University of Iowa

- Spectator

- Monthly News for UI Alumni and Friends

Scientists love finding something new. Solving mysteries and putting together pieces of a complex puzzle are the chief rewards of the scientific life. The scientific method—suggesting an idea about the way something works, then using measurable and observable methods to test it—might seem straightforward enough. But good science rarely works that way.

“People see shows like CSI, where difficult questions are quickly solved and mysteries are wrapped up in a one-hour episode,” says Mark Blumberg, professor of psychology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “They don’t see the obsession, the struggle, the reading,the thinking, the mistakes. The path to discovery almost never follows a straight line. It’s typically more like a drunken walk.”

The motivations to pursue that circuitous path are as varied as scientists themselves, and University of Iowa researchers study everything from black holes to bioinformatics to behavior. But there is a common thread—the sense that science is a rewarding pursuit worth sharing.

“Seeing something never before seen, sharing that excitement with students, watching them conduct an experiment on their own for the first time—that’s what gets me up in the morning,” Blumberg says.

Those mornings are full of variety, as the lives of academic scientists resemble those of small business owners: they must fund their work by writing and submitting grants, a highly competitive process. They also manage laboratory staff and operations, design experiments, write and publish research papers, and teach. Many see patients in clinic and hospital settings. With this kind of hectic schedule, what’s the appeal of academic science?

“I tell my students that in the pharmaceutical industry your role is very defined, fulfilling one aspect of the large process of developing a drug,” says Aliasger Salem, associate professor of pharmaceutics in the College of Pharmacy, whose research involves developing vaccines that stimulate an immune response against cancer cells. “In academia, you take an idea from conception to finish. You can follow your passion. There are many long hours, but it’s worth it for the intellectual freedom.”

“This is not an 8-to-5 job,” says Beverly Davidson, Carver Biomedical Research Chair and professor of internal medicine in the Carver College of Medicine, who studies the molecular underpinnings of fatal neurological diseases. “But if you have drive and a passion for science, if you’re a creative thinker with a strong work ethic, if you have a flair for communicating your ideas on paper and orally, and if you can maintain your enthusiasm through downturns, this is exciting work.”

Diane Slusarski, associate professor of biology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, whose research includes studying calcium signaling in zebra fish, adds a couple more important qualities for thriving in academics.

“You need to be self-motivated, curious, and not afraid to ask questions,” she says. And she reiterates the need for a thick skin. “I tell my graduate students that experiments take time and energy, and that they won’t work more often than they will.”

Learning from those failed experiments is another hallmark of a successful scientist.

“Every day we make new observations and collect new data, and those discoveries might mean that what I assumed was true yesterday isn’t right,” says John Kirby, associate professor of microbiology in the Carver College of Medicine, who studies how bacteria sense and respond to their environment. “It’s very humbling and sometimes painful, but it’s also exciting—it means we know more about that subject, and that past experiments can be reinterpreted in a new light.”

Nonscientists may have difficulty understanding the importance of specialized research topics like Kirby’s or Slusarski’s. But time and again, academic scientists cite earlier research findings, on sometimes unrelated topics, as important in helping them move forward (see story “Fruit Flies and Frog Skin”).

Aliasger Salem puts it this way: “I’m often harnessing the basic science work done by many before me,” he says. “I’m interested in technological development, in formulating drugs, but this work is often built on basic science.”

Why do hundreds of scientists find Iowa the perfect place to engage in the art of discovery?

Kirby cites the Midwestern work ethic.

“Running a lab is a little like coaching a sports team,” he says. “It’s up to me to figure out each individual’s strengths and to design projects appropriately. But it’s important not to just do what’s easiest—students need to be challenged to fill in gaps in their skills. Students at Iowa like to be challenged.”

Salem, who originally came from England but has worked on the East Coast, finds truth in another Midwestern stereotype, one that helps make good science even easier.

“People here are just so nice—they’re readily accessible and more grounded and willing to help,” he says. “It’s not a competitive environment, but one of ‘What can we do together to get good work done?’”

He also notes that the facilities are excellent and staffed by skilled employees.

“The opportunity to work at The University of Iowa is quite stunning, really, ” adds Kirby. “This place allows scientists to flourish.”

—Linzee Kull McCray

with photos by Kirk Murray

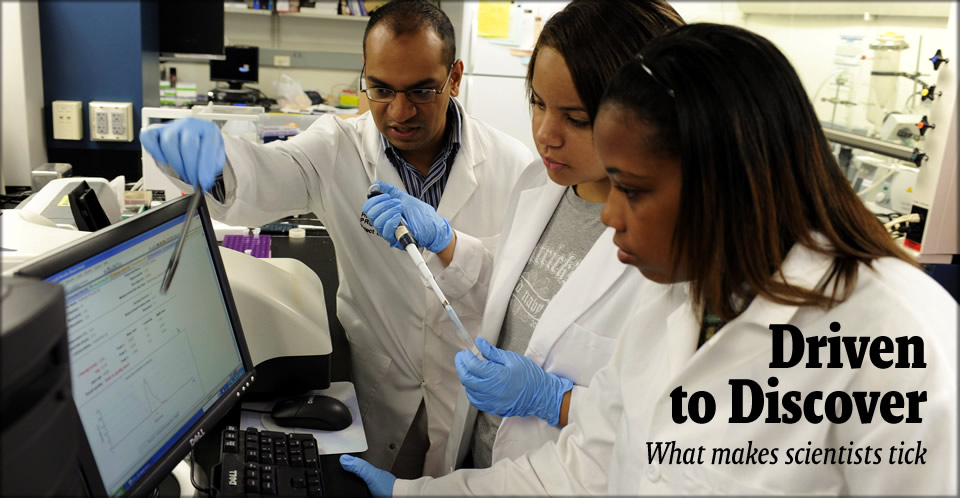

In summer 2009, academic scientist Aliasger Salem, associate professor of pharmaceutics in the College of Pharmacy, worked with UI sophomore and chemistry major Zsalanda Dixon (center) and Keyana Tyree (right), a senior chemistry major from Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University. “I love teaching students and helping them understand the inquisitive nature of the profession,” says Salem. “We’re trying to answer questions that have an impact on our society.”

How obscure discoveries lead to scientific advances. Read more…

Collaboration and mentoring invigorate research. Read more…

Diane Slusarski, associate professor of biology, studies zebra fish, because their rapid growth rate and transparent embryos make them ideal for research on embryonic cell migration to appropriate locations in the body. Still, Slusarksi notes that the path from a lab discovery to a patient’s bedside is lengthy. “Science is often a work in progress,” she says. “It can take five years for an idea in a grant application to be tested and the results published. It’s not about instant gratification.”

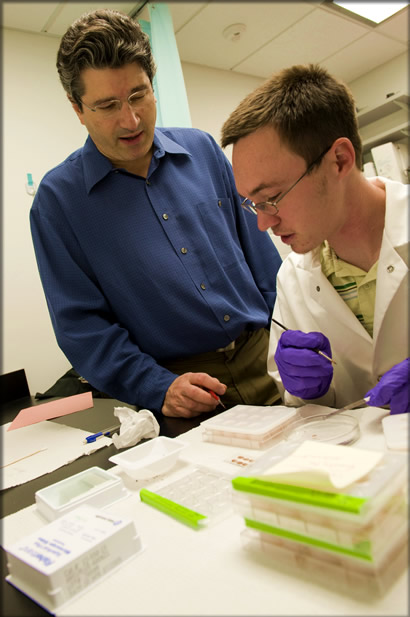

Mark Blumberg, F. Wendell Miller Distinguished Professor in psychology, supervises a graduate student in his lab during an experiment to study changes in brain activity during sleep across early development. “The time I spend mentoring students is not just about teaching techniques,” he says. “It's also to help them understand what the scientific life is all about.”

© The University of Iowa 2009