-

Page Navigation Links:

- Skip to Site Navigation Links

- Skip to Features

- The University of Iowa

- Spectator

- Monthly News for UI Alumni and Friends

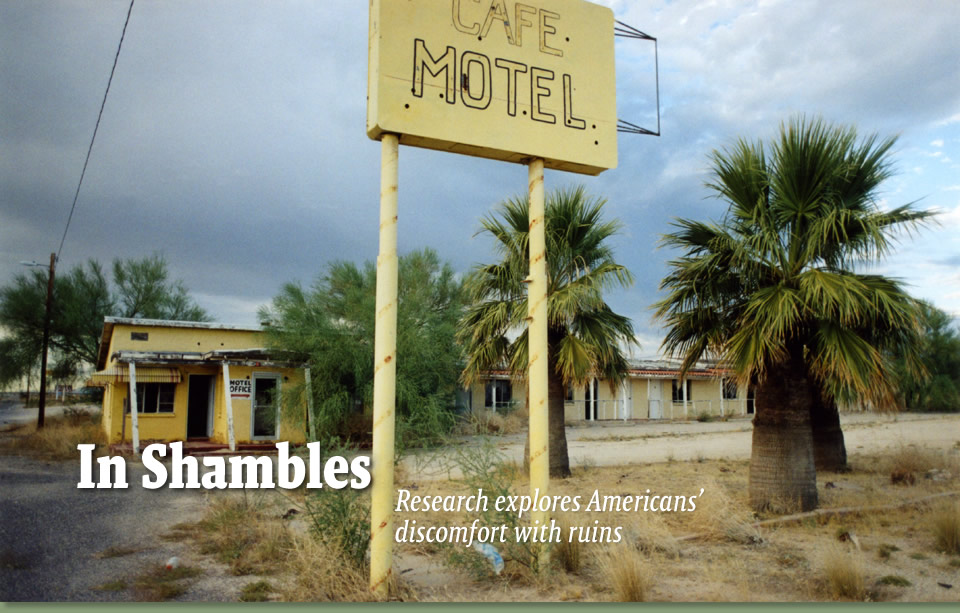

The economic crisis has produced at least one bumper crop: a growing number of damaged, decaying, and abandoned homes, businesses, and office buildings dot the landscape.

A University of Iowa professor notes in his new book that this kind of blight dates back to a much earlier point in history. In Untimely Ruins, published by the University of Chicago Press, Nick Yablon writes that American ruins were a symbol of the country’s economic volatility throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

“Even today, American ruins represent an unstable capitalist economy that produces and destroys simultaneously,” says Yablon, associate professor of American Studies in the UI College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “Americans have associated ruins with failure and viewed them as an embarrassment. For that reason, there’s a tendency persistent to this day to not want ruins around.”

As an example of capitalism fueling its own ruins, Yablon writes of a first generation of Manhattan skyscrapers that were demolished in the early decades of the 1900s, making way for taller buildings that would generate more rent.

“The life span of these 20- to 30-story skyscrapers on Wall Street averaged 15 years,” Yablon says. “This phenomenon of creative destruction led New Yorkers to stop and watch the demolition of those architectural landmarks and to imagine the half-gutted buildings as short-lived ruins.”

The failure of certain “speculative” cities represented another kind of modern ruin. Developers assembled a few log cabins and created attractive panoramas to advertise locales as “cities in the making,” trusting that overseas investors or prospective residents would buy property without visiting.

One such city was Cairo, Ill., promoted as the future “Metropolis of the West” in the 1830s. The unfinished town was wrecked when a hastily built levee failed, forcing residents to flee. When Charles Dickens passed by on a steamboat in 1842, he described Cairo as a “dismal swamp” of mud and debris.

“These ruins demonstrated how fragile American cities were and revealed the chaotic nature of urban growth,” Yablon says. “Cities didn’t necessarily rise gradually; it was often quite the opposite. Cities could take off instantly, flop before they got off the ground, or grow in a start-stop manner.”

Observing the rise and fall of relatively new buildings, 19th-century writers began to envision the ruins of the future. The 50-story Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower—New York’s tallest building in 1909—was the target of such musings in mass-circulation magazines and in the emerging genre of science fiction.

A Scientific American cover photo illustrated how far the tower’s rubble would extend if it toppled, suggesting that it would crush every building for three blocks. In popular novels, short stories, and cartoons, the magnificent building was submerged in the ocean, struck by a comet, bombarded by foreign airships, or besieged by a horde of monstrous creatures.

Even the imagined depictions of ruins tied back to capitalism.

“They used these stories to reflect on the contemporary issues of labor conflicts, which were mounting in the late 19th century,” Yablon says. “Some of the stories described future historians or archaeologists coming across the ruins of Chicago or other industrial cities and finding evidence of workers’ uprisings against their capitalist employers.”

Another peculiar feature of all these ruins was their unexpected emergence. Europeans embraced the ivy-lined abbeys in Britain, and the crumbling stone coliseums and statues of ancient civilizations like Rome or Greece. But in the young, growing republic of America, a collapsed cement building or an abandoned neighborhood felt shockingly premature.

“There’s something more romantic and pleasurable about traditional ruins. One can safely say that’s the past, and our own civilization is thriving,” Yablon says. “American ruins didn’t evoke that sense of pleasure. They felt incongruous, untimely.”

—Nicole Riehl

© The University of Iowa 2009