-

Page Navigation Links:

- Skip to Site Navigation Links

- Skip to Features

- The University of Iowa

- Spectator

- Monthly News for UI Alumni and Friends

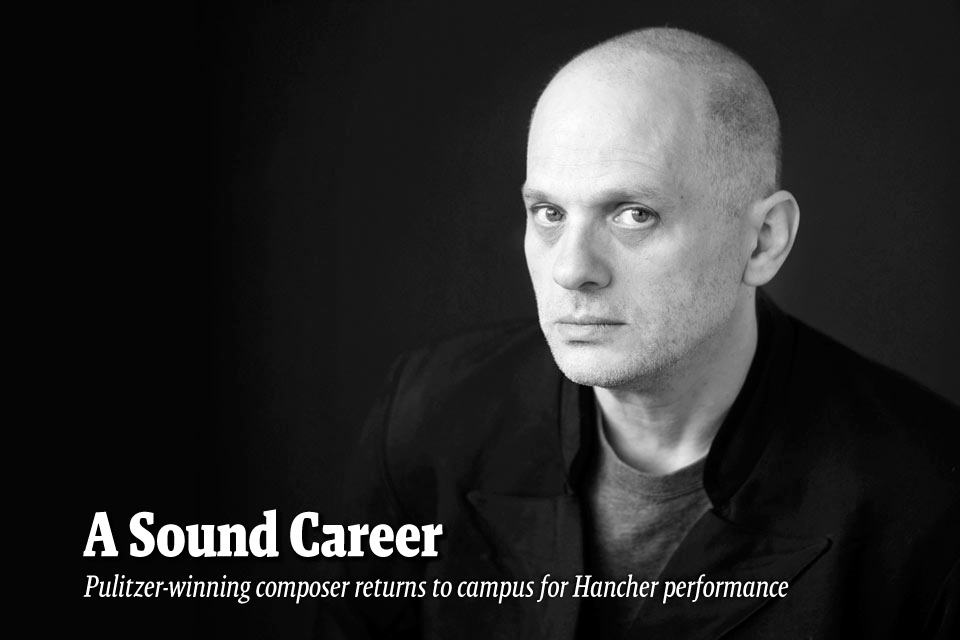

Composer David Lang’s University of Iowa homecoming this fall came a little later than it did for most alumni. But it was memorable both professionally and personally.

Lang (M.A. ’80) returned to Iowa City in mid-October, a visit that allowed him to reconnect with the campus and city that, in the late 1970s, helped launch him on a musical career that brought him critical acclaim, capped by a Pulitzer Prize in 2008, and at least enough fortune, as he notes, “to feed my family.”

He came back for an Oct. 11 performance of love fail, which he wrote for Anonymous 4, an a capella musical group that focuses on medieval and ancient music. The performance is the latest in a series of Lang works commissioned and co-commissioned by Hancher.

Lang also experienced campus with a new perspective—as the parent of an undergrad. The oldest of his three children, Ike, is a first-year student at Iowa, and Lang had a chance to make sure “he’s eating properly.”

Lang recently spoke with Spectator about what drew him to music and to Iowa and how he starts the creative process.

You’ve said love fail was developed for Anonymous 4. How do you go about the creative process—what to write and who’s going to perform it?

It’s so interesting that you put those things together because that’s what goes through your mind. There’s what you want to do and then someone has to perform it. So what happens is as a composer, you’re constantly trying to imagine the place where what you’re interested in can be translated for somebody else who has very different ideas or talents.

If I’m doing something with Anonymous 4, what I get to do is to think, “Where are my musical interests intersecting with theirs? How can I tell a story that’s important to me that also might be important to them?” Because they dedicate their lives to studying and performing music that may be even a thousand years old, I wanted to do something that way too. I thought if I could tell a story that reminded them of the stories they are used to telling and use their voices in a way that they’re comfortable with, then we’d be able to explore where our worlds interact.

That’s one of the interesting things about being a composer. Part of it must be lonely, and yet so much is about collaboration.

I don’t ever believe that the point of music is to make something just for myself. It’s so hard to write a piece of music. And if you were just going to do it to please yourself, wouldn’t you do something easier? Wouldn’t you do something that wouldn’t cause you so much anxiety? The point of making music is to communicate something. It’s to say “I have something I want to tell you, and I’m going to build a doorway so you can get to it.” And sometimes it’s interesting to build a door that a million people can go through. And sometimes you go with a door that a hundred people can go through. But if you’re not going to build a door, there’s no point in doing it. I think this goes with every single piece. What is the conversation that a listener is going to want to enter into with me?

When you were young, what did you want to be when you were older?

I always wanted to be a composer. That’s it. I started writing music when I was 9. And it was completely by accident. I saw one of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts. My parents were not musical. Nobody in my family really listened to classical music, and we didn’t have instruments in the home. It was just sort of by luck that I ran across this Young People’s Concert, and that my school actually had some instruments that I could borrow.

What brought you to Iowa City and the University of Iowa?

I followed a teacher. I went to Stanford as an undergrad, and there was a teacher in composition at the University of Iowa named Martin Jenni, and he had come to Stanford as a leave replacement to teach for a semester. And I just thought he was amazing. He knew a lot of stuff that I’d never heard of before. So when I thought about grad school, I went to Iowa. I was happy I did. It was really a kind of golden age. I really loved it.

What drew you away from Iowa City?

I always knew from when I was a kid that I was going to go to New York. When I was a senior in high school, I was interested in all these weird composers that not many people at that time had heard of before. Steve Reich, Philip Glass, La Monte Young, and John Cage. I just thought that this was the coolest and weirdest thing, that people were experimenters in classical music. What a great idea. And somebody told me, “Oh, you know the interesting thing about all the composers you like is that they live within a few blocks of each other in Manhattan.” So I remember thinking—I’m going to live in that neighborhood. And now I’ve lived in that neighborhood for 32 years.

Do you have any advice for music students?

I think there are a couple of really important things. You need to be always really curious about what’s going on in the world musically—about everything in the world, actually—but especially about the musical part.

And you need to be honest with yourself about what it is you really want to do. You should try lot of different things and be really honest with yourself about which of them give you pleasure, or whether or not you’re good at them, and whether or not you think if you worked really hard you could be better at them. For young musicians, that’s the hardest thing, to be critical about what it is you can do as compared to what it is you want to do. That’s probably the hardest thing for anybody in any walk of life.—Steve Parrott

Photo by Peter Serling, copyright 2009

© The University of Iowa 2009